Gentrification has given Brooklyn a beautiful makeover, but under the surface lies the ugly problem of homelessness and displacement. It’s now the least affordable borough due to gentrification and its hostile takeover of Brooklyn neighborhoods is pushing the poor out on the streets while giving the rich a new territory.

Homelessness is a citywide concern, with 60,484 people sleeping in New York City shelters each night, according to the Coalition for the Homeless. The city is trying to provide apartments with New York City Housing Connect, a portal where users can apply for affordable units throughout the city. However, the number of apartments available greatly outnumbers the amount of applications. As noted in a New York Times article, it was mentioned that a building in Brooklyn at 59 Frost Street had 38 affordable apartments, but received over 80,000 applications for those units.

With the number of people without a home at the highest that it has ever been, Mayor Bill de Blasio has also introduced an affordable housing plan for the city as well. Labeled “Billification,” the $41 billion plan will set aside 200,000 housing units in the next 10 years. The number of apartments reserved for very low-income residents will increase by 200 percent.

“That’s half a million people,” said Norvell Wiley, press secretary for the mayor’s office. “That’s the size of Miami or Atlanta.”

In de Blasio’s plan, for very low income families that make less than $25, 151 annually, there will be 16,000 units, four times more than the Bloomberg administration supplied, according to Wiley. People with income between $25, 151 and $41, 950 will have 12 percent, or 24,000 of the 200,000 units, reserved for them. People with income of $41, 951 and $67, 120 a year are considered low income and will have 116,000 units, or 58 percent, of the housing reserved for them. The rest is divided up between residents who gross $100,000 or more annually.

Brooklyn is also making an effort to provide non-pricey housing. Atlantic Yards, a plan for affordable housing that accompanied the development of the Barclays Center, is supposed to bring 2,250 affordable units to the borough by 2025. In the two buildings currently under construction, two-thirds of the 600 apartments are reserved for families of four who rake in $100,000 a year, with rents at $2,600 a month. Another 300 apartments are set aside for families who make $130,000 a year. These “affordable” prices are not feasible to Brooklyn residents who have a median income of $44,850.

Besides affordable and luxury housing, there are apartments at market rate, but even those are a bit steep. According to Rapid Realty, Inc. realtor Raymond Ruiz, a single bedroom or studio in Bed-Stuy has a rent of approximately $1,300 a month while a two bedroom apartment goes for between $1,600 and $1,800 a month.

Dr. Alex Schwartz, a professor in urban policy at The New School, agrees that there is a link between gentrification, homelessness/displacement and the lack of affordable housing.

“Gentrification can cause rents and home prices to increase, making housing less affordable,” he said. “It can also motivate landlords to violate rent stabilization and other laws and harass low-income tenants to leave their homes, enabling them to rent at higher rents to more affluent tenants.”

When gentrification hits an area, bodegas and “moms-and-pops shops” are replaced with with five-star dining, upscale supermarkets and chic boutiques to a lower income neighborhood. But with these amenities comes young professionals and families with higher incomes. Landlords take notice and current residents become throwaways.

“I don’t mind if people want to move in but let us stay in our apartments,” said Linda Hiwot-Williams, a Brooklyn resident who has been displaced from gentrified Flatbush to New Jersey. She and her husband had a rude awakening last winter when their landlord suddenly evicted them one morning without reason. This was a shock mainly because she said she and her husband had paid rent every month during the eight years they had lived there.

“We were just getting out of bed and we heard this big thumping on the door and she said ‘Alright you got 10 minutes to get out!’ You know how that felt?” she said in a Flatbush apartment off of Rutland Avenue.

After her landlord took her to housing court in efforts to get her out, Hiwot-Williams was allowed to stay, but only for two weeks. The gentrifying of Brooklyn neighborhoods and lack of affordable apartments caused her to hit many dead ends during her search for a new home. Not only does she work as a full-time substitute teacher, she is also a painter and receives Social Security benefits. But even with three streams of income, she was denied an apartment in Lefferts Gardens, a development for which she qualified.

“They said the only way I could get it is if I paid rent a year in advance,” she said. “What is that?”

Hiwot-Williams had no choice but to take one of her painter friends up on their offer for an apartment in New Jersey since it was her last resort.

But many New Yorkers who are displaced due to gentrification do not have anywhere else to turn to besides an overcrowded shelter or the streets. Affordable housing opportunities are scarce, yet high in demand.

Hiwot-Williams said she once tried to sign up for affordable housing at a local Brooklyn church and “the line was around the block.”

“Place wasn’t big enough to hold everybody,” she said. “So I signed up to get notices for affordable housing. No responses.”

When it comes to affordable housing in New York City, the definition of affordable isn’t universal.

“It’s a joke,” said Scott Andrew Hutchins, housing campaign leader of community organizing program Picture the Homeless about de Blasio’s “Billification” plan. “The affordable housing he’s talking about isn’t affordable to most people.”

Kyle Reid, 28, has been homeless for six months. Though he says he is more worried about his job hunt rather than his housing search, the affordable housing plans do not sound too appeasing to him.

“I’d rather live in a basement in Canarsie,” said the Flatbush native. “You need about $1,200 now just to get a decent apartment now. I don’t even know how much I can afford right now.”

When people with a more flexible income migrate to places like Brooklyn, Equality4Flatbush campaign founder Imani Henry said that landlords see dollar signs and become “sinister” in order to get current tenants out.

“[Landlords] can get $2,000 for your apartment now,” he said. “They can lie.”

“Picture the Homeless” activist Maria, who didn’t want to give her last name, said that landlords stop fulfilling their duties in hopes of vacating their properties.

“The landlords are not doing the repairs to the point where they have so many violations to the point where tenants have to go into the shelter,” said the 44-year-old.

Henry said he has encountered many people who fell victim to greedy, unfair landlords who wanted to push current residents out at any cost to rent to the new high-income gentrifiers.

“They’ll go into your house at night and rip the floor boards. They take you to court for non-payment because they haven’t recorded your checks.”

Hiwot-Williams also complained about “greedy landlords” being agents of homelessness.

“They are not helping the situation,” she said one week before she moved to New Jersey. “They do things to make people want to move out. They raise the rents and some of them raise the rents more than 100 percent.”

Ruiz claimed that landlords do what they can for their tenants according to the rent that they are given.

“Not every landlord is like that,” he said over the phone. “I see landlords doing more for their tenants now than they could before because now they are getting what they been asking for.”

Wiley said that the Mayor’s administration has taken notice of shady landlords who illegally push tenants out and have programs in place that will now protect residents for the first time in New York City’s history. They have put $36 million into a program that will provide lawyers, free of charge, to those who are being pressured by landlords to move from their newly zoned area. They also have a task force with the attorney general that will address landlords that illegally raise rents, demolish and renovate apartments to try to get tenants to leave.

While some notice the link between gentrification and homeless/displacement, it isn’t easily recognizable to everyone. Dr. Ingrid Gould Ellen, the director of New York University’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, suggested that residents of gentrified areas are usually happier with the changes in their communities.

“Residents living in low-income neighborhoods that see increase in income generally report greater satisfaction with conditions and services in their neighborhoods,” she said via email correspondence. A 2011 study conducted by the Furman Center found that “original residents are much less harmed than is typically assumed.” It was also concluded that residents “do not appear to be displaced in the course of change, they experience modest gains in income and they are more satisfied with their neighborhoods in the wake of change.”

Henry begs to differ and could not identify any positives of the process.

“It’s not an inevitable thing. It doesn’t need to happen. How does it benefit society?” he asked.

Ruiz could name a few benefits. He said that gentrification brings more opportunities into communities, which leads to more jobs, more income and safer streets.

“Maybe somebody is not able to find a place or the prices are a little bit higher but it also changes the neighborhood from being a high crime rate area to a favorable area where people want to move to.”

But that’s the problem. High income outsiders are moving into these communities, to the delight of landlords and luxury housing developers, and the working class and poor driven away because they aren’t desirable tenants.

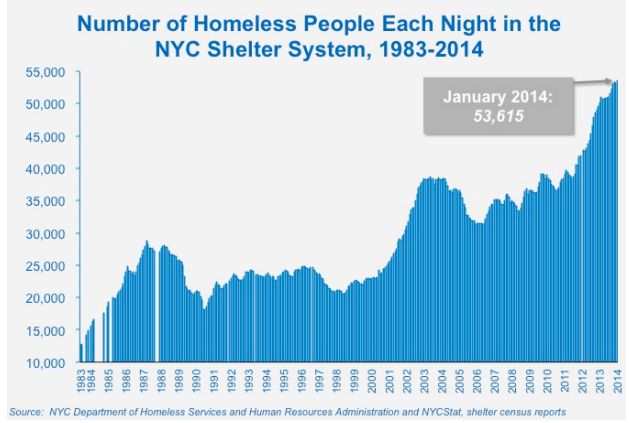

This crisis didn’t happen overnight, though. The foundation for the city’s homelessness dilemma was laid back in 2005 by former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration. Bloomberg concluded that people were becoming homeless on purpose in order to get priority New York City Housing Authority apartments, so he made what he thought were necessary changes, not knowing he was planting the seeds for a crisis.

“Before, if you were homeless and living in the shelters you had priority over other groups,” said Gabriela Sandoval, policy analyst at the Coalition for the Homeless. “[The homeless] had the same priority as domestic violence victims but because he thought that this was an incentive for people to enter the homeless shelter system, he took it out and he thought the numbers were going to go down. However, the exact opposite happened.”

From that year on, the city’s homelessness rate rose consistently for the next 10 years. The figures changed from 36,599 in 2005, to 39,365 in 2011 and 53, 615 in 2014.

While Bloomberg’s changes wreaked havoc on the lives of poverty stricken families, gentrification was creeping into the New York City, mainly Harlem and Brooklyn.

While Bloomberg’s changes wreaked havoc on the lives of poverty stricken families, gentrification was creeping into the New York City, mainly Harlem and Brooklyn.

“We’ve been in a housing crisis,” Henry said. “This is not a new development. The shelter system has been at overload. It’s just that gentrification has pushed it to the next level.”

“Picture the Homeless” has conducted research revealing that each borough has thousands of vacant properties that can be used to build affordable housing.

“There is so much vacant property in New York City that real estate developers don’t want you know about it because they are sitting on it waiting for rent stabilization to expire and for the value of the property to go up,” Hutchins said.

Their 2013 report found that Brooklyn had the most vacant property among the five boroughs. With a total of 1,623 vacant buildings and 1,412 lots, 70, 932 people could be housed.

Hutchins, who has been homeless since 2012, said that a solution that could successfully address the housing crisis is having community land trusts, which is land that is “owned by the people who live there.”

“The development of that land has to be done under the auspices of the people who live there so people can say this is what we need here, this is how much the housing has to cost so you develop housing at this cost or you don’t develop here,” he said. “But in order to do that we have to get the land.”

There is a glimmer of hope for homeless families, though. According to Sandoval, the de Blasio administration has set aside 750 units of public housing apartments for homeless families. Last September, they launched the Living In Communities (LINC) program, a rental assistance program that offers five different types of temporary vouchers that help homeless families transition into stable housing from the shelter system.

Mayor de Blasio’s administration is hard at work not only trying to preserve affordable housing but to ensure that every new luxury building has mandatory affordable units set aside.

“You can build that luxury building but 25 to 30 percent of it needs to be affordable for people who live in the neighborhood,” Wiley said.

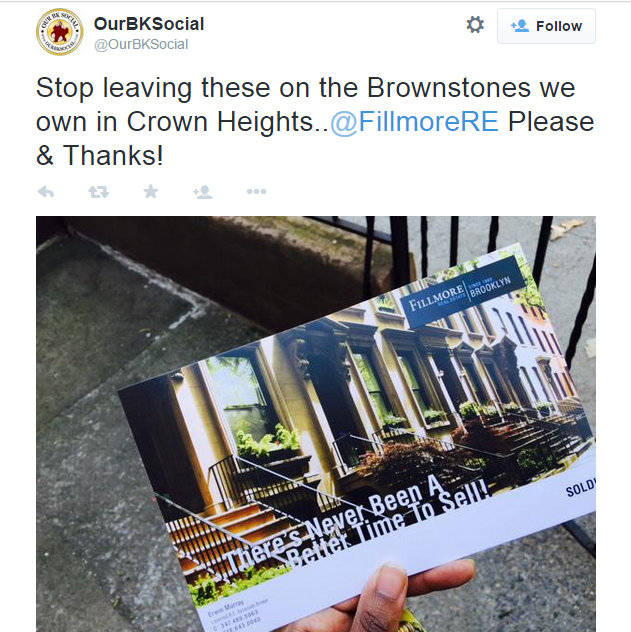

As far as the gentrification of Brooklyn, developers are steadily moving into the East New York and Crown Heights sections. Real estate companies have been littering these areas with flyers offering homeowners cash for their homes or trying to outbid potential home buyers and offering money the same day.

“I wonder how far they are going to take this,” Hiwot-Williams said.

https://gentrificationandhomelessinbrooklyn.wordpress.com/

Published in May 2015 as a capstone presentation